The case of Diary of an Oxygen Thief is highly reminiscent ofThe Cruelty, a YA novel by Scott Bergstrom that landed a six-figure advance and movie rights after being self-published. (YA Debut Gets Six-Figure Deal: How did Scott Bergstrom Do It?)

Both authors had a background in advertising and understood marketing. Both positioned themselves as independent publishers. (In Scott's case he formed a LLC.) But in important ways, their stories diverge. Unlike Scott, the author of Diary (Anonymous) peddled his book directly to bookstores. He started small, but eventually got his book into Barnes & Noble. He then focused heavily on advertising.

Living in New York City meant that Anonymous had an advantage when it came to posters and bookstores, but considering the wide reach of the Internet, almost anyone with an understanding of their potential readers could do what Anonymous did.

_____________________________

How 'Diary Of an Oxygen Thief' Went from Self-Published Obscurity to Bestsellerdom

By Rachel Deahl, Publisher's Weekly

You may not know what Diary of an Oxygen Thief is about, but you might have heard the title. Or maybe you saw a picture of the book on Instagram, or read a discussion of it—positive or negative—on Twitter. And that’s by design: a design carried out by the book’s anonymous author over 10 years.

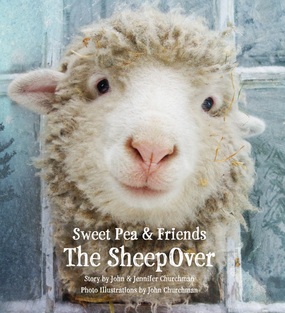

The slim novel, which details the travails of a broken-hearted, alcoholic, and bitter misogynist (who is also an unreliable narrator), was self-published in 2006. After selling nearly 100,000 copies—predominantly in trade paperback and e-book—the book was acquired by Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books imprint in May, and re-released by the Simon & Schuster imprint on June 14. In its first three weeks on sale, the title has gotten off to a respectable start, selling roughly 14,000 copies, according to Nielsen BookScan. The book’s unlikely rise, from underground hit to Big Five-published novel, is due predominantly to the marketing efforts of its anonymous author. He pulled off a savvy publicity campaign that prioritized, above all else, getting the book’s title shared on social media.

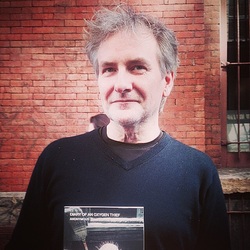

The author, who asked that his name be kept out of print, spoke to PW from his apartment in New York’s East Village about the long, strange trip of publishing —and promoting--Diary.

A Brit who honed his advertising craft at some of the major agencies in London, then New York, the author self-published the novel in Amsterdam in 2006. At that time he was working for an ad agency in the Netherlands and, after having the book rejected by a number of U.S.-based literary agents, a friend of a friend offered to print him 1,000 hardcover copies for free. Although the author hadn’t intended to self-publish, he decided to make use of the copies he suddenly had. After taking one into a bookstore in Amsterdam, he was pleasantly surprised by the fact that he got the title on the shelf. “[The bookseller] held [the book] up and shook it,” the author said. “I think he had this fear, because it was self-published, that it was poorly made and would fall apart. He never looked at the text. He then said he’d take three copies.”

Soon the author was taking requests for bigger orders from the Amsterdam bookshop. He also started getting copies into bookshops in other cities, such as Paris’s Shakespeare & Co.; the stores, he noted, all catered to young hipsters, whom he considered his target market. After moving back to New York City, the author, who was then working freelance advertising gigs, felt emboldened by the success he had selling, and distributing, the book in Europe. He decided to do a 5,000-copy print run of a new trade paperback edition, and to focus almost entirely on selling it. “I was getting just about enough orders that, if I lived a simple life, I could pull it off,” the author said.

Amping up his promotional efforts, the author hit several indie bookstores in N.Y.C., gaining particular traction at Spoonbill & Sugartown in Williamsburg, Brooklyn; the East Village’s former St. Mark’s Bookshop; and Nolita’s McNally Jackson. To get copies into Barnes & Noble, the author posed as an independent publisher and pushed the title through the retailer’s small-press program. (No meetings were required with B&N; everything was done via email. The author, calling himself V Publishing, told the retailer that his house was targeting the “hipster market, the most elusive of all segments” and would rely on guerilla marketing. He also showed the retailer some YouTube clips he’d made promoting the book. B&N placed an initial order of 100 copies.)

Intent on building underground buzz for the book, the author focused on promotional efforts that would make people google the book’s title. From his limited sales in bookshops he felt confident that he could land readers by getting the book’s cover (which features a picture of a snowman whose carrot nose has been repositioned to look like a penis) seen, and its title shared.

Read the rest of this success story HERE.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed